Theoretical, actual, and erosion of access

What is accessibility and what does it mean? More importantly, what do you need to do to become accessible?

Even though accessibility is one of the biggest barriers to people with physical disabilities, the term is still unclear to many.

An accessibility feature, in its simplest form, is something that reduces barriers to make life better or easier for people, whether they have disabilities, strollers, or even large boxes and packages.

Over the years, we have seen regulations and laws that have shaped accessibility around the world. However, even with those in place, there continues to be issues.

So how do we know if something is truly accessible?

Ultimately, almost every accessibility situation falls into three main categories, which can be used to determine how useful an accessibility feature is and whether there are ways to improve it.

Theoretical Accessibility

Almost every accessibility feature undergoes a planning stage. Things are mapped out and measured and it is determined to be accessible according to certain criteria or regulations.

These accessibility features are technically accessible, but there is a chance that they are not entirely practical to use, often (but not always) due to location.

An example could be an elevator tucked away in a corner of a building, rather than closer to everything else. Another situation could involve a ramp that forces someone to cut through lanes of busy pedestrian traffic to reach it.

Theoretical accessibility without efficiency or practicality makes it appear as if there was no testing phase. While the accessibility feature may technically still be accessible, it fails to make life easier for those who use it.

Actual Accessibility

“Actual accessibility” and “theoretical accessibility” are not mutually exclusive terms, but when there is a difference between the two, it is strikingly clear.

Actual accessibility makes accessibility features appear to have been tested for efficiency. This could involve thinking about how to maximize convenience. For example, if an elevator door is not far away from a ramp, that is an example of actual accessibility. (An elevator that is quite far from a ramp would be an example of “theoretical accessibility.”)

It is important to note that actual accessibility is not always related to bylaws, regulations, or building codes – in fact, it goes beyond them. Bylaws and regulations focus on compliance, but compliance does not always specify issues such as ramps interfering with traffic flow of stair users.

Erosion of Access

This term originates from Vince Miele of the Richmond Centre for Disability to describe how the maintenance (or lack thereof) of an accessibility feature can impact its accessibility. Examples may include crumbling sidewalks or elevators that do not get repaired – essentially compromising safety or even the usefulness of the features.

Even houses need a touch of paint once in a while, or other upgrades to the roof and windows. Ramps, elevators, and other accessibility features are no different. Without repairs and fixes, they will simply sit neglected and their usefulness will eventually decline, regardless of how well they worked when first implemented.

Case study: Parking and restrooms

Jessica shops at a local supermarket that has been quite good about actual accessibility inside the store, such as card machines that are height and angle adjustable for those in wheelchairs.

However, the two wide and ramped accessible parking spots outside the store are now constantly being occupied illegally; the two “disabled parking only” signs that used to mark those spaces were neglected and eventually disappeared due to erosion of access, and now only two empty poles stand in their place.

Elsewhere around town, she also went to a restaurant, where theoretical accessibility was available in the form of restrooms with accessible stalls. However, erosion of access also occurred here as the extra space in the restroom has been used as storage space over time, making its accessibility features useless.

Case study: public transportation

Bucky uses a wheelchair and occasionally takes public transportation in Vancouver. He finds it theoretically accessible for the most part. However, there is one pet peeve that annoys him.

One of the subway lines in town uses trains from Hyundai, which he is familiar with since he used to live in that company's home nation of Korea. Over there, the accessible seating is located at the fronts and ends of the trains. However, Vancouver’s public transit agency has decided to put it closer to the middle.

The stations’ configuration exposes the weakness of this layout, as the stairs are located near the middle of the platform – so any wheelchair users exiting the train will land next to the stairs and would be bombarded with able-bodied passengers heading for the exits.

For Bucky to exit the station, he would get off the train and have to fight against the mass of humanity heading towards the exits, before he even comes close to the elevators – which are located at the ends of the platform.

This lack of actual accessibility poses safety and efficiency problems, as he could not exit the station efficiently and there is always the risk of the crowd of people knocking him off the platform and onto the tracks or against a moving train.

How do we solve this problem?

Theoretical accessibility is always a must-have, since it is part of the planning process. However, plans must also include consultation with accessibility experts or those who benefit from accessibility features on a daily basis – these people are able to spot the small details that could make a world of difference, but are constantly overlooked by others. This helps maximize the potential for actual accessibility.

After implementing accessibility features, they should be tested with real-world situations in mind to achieve actual accessibility. In Jessica's case, the supermarket realized that people who are shorter could have an issue with lighting glare on card machines’ screens, so the decision was made for angle adjustability. In Bucky’s case, things could have been improved if testing had included the possibility of a crowded subway station.

Erosion of access can easily be achieved by combining that with the general maintenance demands of the location. Every place needs some sort of upkeep, whether it is a public park, sidewalk, business, or even a home. By including accessibility features as part of the routine, we can ensure that they will be useful for many more years to come.

Interested in learning more about accessibility?

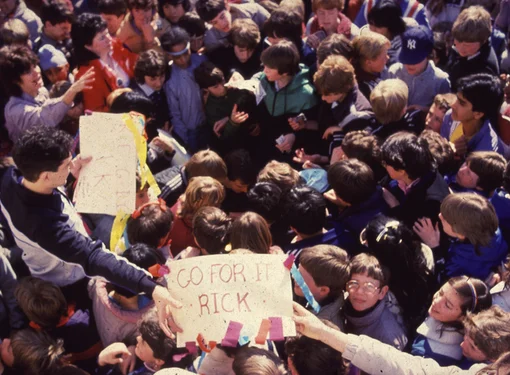

Marco Pasqua, Marketing Community Manager for the Rick Hansen Foundation's accessibility tool Planat™, will be a featured presenter tomorrow (2014 December 3rd) at the Roundhouse Community Centre in Vancouver, British Columbia, as part of the United Nations' International Day for Persons With Disabilities festivities. Admission is free and the event runs from 3:00pm to 8:00pm.

The Roundhouse Community Centre is located at 181 Roundhouse Mews in Vancouver (at the corner of Davie Street and Pacific Street). It is close to the accessible Yaletown-Roundhouse Station of the Canada Line SkyTrain.