What APN 2025 Taught Us About Designing for Belonging

After Marjorie Aunos sustained a spinal cord injury, one of her first hopes was to return to something beautifully ordinary: a shopping trip to buy clothing for her 16-month-old son. The outing was meant to mark a return to normalcy. Instead, it was an upsetting experience of how far the world still has to go.

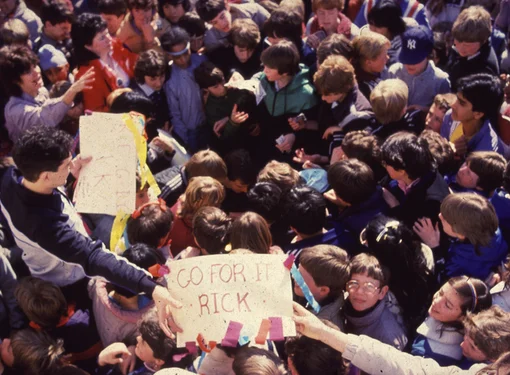

“Getting clothing for my son became an obstacle course,” Marjorie, who uses a wheelchair, told the crowd during the opening session at the 2025 Accessibility Professional Network (APN) Conference on March 27 and 28, presented by Accessible Employers and Vancouver International Airport (YVR) and hosted by the Rick Hansen Foundation at the Vancouver Convention Centre and online.

Her story was met with nods of recognition. More than 522 people attended this year’s APN — the highest number in the conference’s history — to explore how accessibility can transform not only our physical spaces, but our systems, policies, attitudes, and lives.

The conference theme, Building for People, wove through each session. For too long, accessibility has been framed as a legal obligation or a box to tick. But the human stories and solutions presented at this year’s APN conference pointed to the fact that accessibility is not just a feature. It’s a framework. It’s not about fixing individuals, it’s about fixing systems. And it’s not just about ramps and bathrooms. It’s about creating a seamless journey to create a world where everyone belongs.

Accessibility as a Systems Issue, Not a Silo

In the Day One Keynote, Making a Built World, Complex Systems Strategist for ATCO SpaceLab, James Stauch delivered a wide-angle view of the social and environmental landscape: rising inequality, aging populations, climate disruption, and declining trust in institutions. Accessibility, he argued, is not peripheral to these challenges — it is central to how we respond.

“Accessibility isn’t just about regulations,” James said. “It’s a systems issue embedded in how we build our cities, design our technology, write our policies, and relate to one another.”

Too often, the burden of navigating inaccessible environments falls on individuals, rather than on the systems that exclude them, a statement that echoes the medical model of disability. This must change. Over 60% of Canadian retail spaces remain inaccessible to wheelchair users – case in point, Marjorie’s story. Most small and mid-sized businesses are owned by able-bodied people, James pointed out, designing for a world they know — not the world as it is, which includes 1 in 4 Canadians with disabilities.

As James emphasized, systems are not immutable. They’re human-made. And they can be remade. The takeaway from his session: reframe problems as opportunities and embed inclusion into every decision. Advocating for change doesn’t have to be perfect, just persistent. An oft-repeated quote from the conference, originating from Tammy Morris, Accessibility & Neuroinclusion Leader from EY Canada, applies here: "Think Big. Start Small. Scale Fast."

The ROI of Belonging

One of the most compelling themes to emerge from the conference was a shift from “inclusion” to “belonging.” Ingrid Palmer, a speaker on the Lived Experience Panel, drew a clear line: “Inclusion and belonging are sometimes used interchangeably but they are not the same. Inclusion involves the actions we take; belonging is the outcome that we desire.”

And belonging, as it turns out, is good business. Studies show companies that embrace accessibility outperform their peers. But the real return isn’t just economic. It’s human.

Marco Pasqua, APN Master of Ceremonies, is a father who uses a wheelchair. During this session, he described visiting an inclusive playground for the first time. “I could wheel right to the top of the slide and push my daughter down,” he said. “Not my wife. Not a family member. Me.” He was 36 years old at the time, and the everyday experience was memorable because it was the first time he’d seen the top of a slide since he was six.

These moments of full participation, of joy, of being part of your own family’s story are what accessibility makes possible. As Ingrid reminded us, access is not just about infrastructure. “It’s about attitudes. It’s about being seen and known.”

Designing for the Whole Person — Mind and Body

Day Two’s Designing for the Mind session offered a powerful critique of the ways traditional architecture and planning fail people with cognitive and invisible disabilities. Claudia Salgado, Honorary Research Fellow, University of Stirling, noted that decisions are often made before architects are even at the table, reducing design to a checklist of metrics: square footage, number of beds, efficiency targets. “Jugglers of needs of agendas,” she said of the predicament architects sometimes find themselves in.

The discussion hosted by her and Simon Fraser University Professor Habib Chaudhury made clear that access must include room for emotional and mental well-being. For people living with dementia or sensory processing disorders, disorientation can shrink their world, limiting their autonomy and increasing anxiety.

“Space is only meaningful when it’s in use,” Claudia said, pointing to the disconnection between design intent and lived reality. “If you cannot design a space where everybody can come and use and be… you are creating a design of apartheid.”

Small Moves, Big Shifts

Despite the scale of the challenges around barriers, the conference brimmed with examples of practical solutions and small wins with big impact.

The Workplaces and Accessible Employment session showcased a wealth of lived experience from speakers Maureen Haan (President & CEO, CCRW), Tammy Morris (Accessibility & Neuroinclusion Leader, EY Canada), and Yat Li (Associate Director, Accessible Employers).

Highlights included:

- Pointing out the persistent urge to Google someone’s disability to look for a one-size-fits-all instruction manual instead of a dialogue. “We are not single-layered individuals. People want to be recognized for their skills first not have the focus on finding out what their label might be.”

- Flexibility is key. Whether it’s a preferred workstation or dimmable lighting, “People don’t need everything — they need something that works for them.”

- There are technologies like hearing loops — easy to install, low-cost, but transformative for those with hearing loss who wear hearing aids or cochlear implants. Contrasting paint colours to increase ease of navigation for those with vision loss. The list goes on.

Co-Creation Over Consultation

At the Tom and Ruth Harkin Center in Des Moines, Iowa — now one of only two RHF Accessibility Certified Gold buildings in the U.S. — every design choice was shaped by lived experience. RHFAC provides a framework to measure meaningful access, provide a roadmap for improvement, and celebrates an organization’s commitment to accessibility.

The Tom and Ruth Harkin Center, home of The Harkin Institute for Public Policy & Citizen Engagement at Drake University, aims to serve as a model of inclusion and accessibility to public policy research and citizen engagement. The Center opened in 2020 and, rather than design for users, architect BNIM designed with them. This process is especially notable as the building is named for U.S. Senator Tom Harkin, the primary author of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

When a Deaf user requested open sightlines for communication and a blind user expressed concern about disorientation in wide-open spaces, they didn’t leave the conflict to the design team. They worked together to find a middle ground.

“It wasn’t about compromise,” Daniel Van Sant, Director of Disability Policy, The Harkin Institute, said. “It was about co-creating something better.”

The Culture Shift

There was something different in the air at APN 2025. Maybe it was the record turnout. Maybe it was the brilliance of the speakers. But more likely, it was a sense that we are on the cusp of a new chapter; doubling-down on working toward a brighter future in a time when inclusion is being distorted, defunded, and deliberately misunderstood in the political realm.

Pointed out Maureen Haan: “We don’t smoke in workplaces anymore. Women actually work outside of home now. We wear seatbelts in our cars… So, we know that changes can be made when we put our minds to it.”

Accessibility isn’t a one-time fix. It’s an ongoing process of noticing, listening, and making flexibility a normal part of life to reflect the diversity of human lives. As Claudia Salgado reminded attendees, “Not everyone with a disability wants to be an activist.” Nor should they have to be. It’s up to the rest of us to build an accessible world.

In the end, it’s not just about how wide the aisles at a clothing store. It’s about who is welcomed in and who is still lingering on the edges, waiting for an invitation.