Pride despite prejudice: Overcoming bullying with a disability

Albino. Snow White. Grandma. Four eyes.

These are just some of the names I was called growing up with albinism, a rare genetic condition that causes light skin, hair and visual impairment. It wasn’t the names that hurt the most – it was the lack of respect and kindness from people I thought were friends.

One day, when I was 10, I was sitting in my class when my teacher gave us a math exercise to do before leaving the room. Before I could get a pencil out to start the worksheet,, a girl at my table snatched my pencil case and threw it to her friend across the room. Soon, it bounced from person to person, all who laughed while I pleaded to have it back. I sat there, cheeks burning with shame, while my other classmates joined in the laughter or sat there in uncomfortable silence. I felt completely alone.

I’m not alone in my experience of bullying, though. In Canada, 1 in 3 teens have experienced bullying, according to Canadian Institute of Health Research. Children and young people with disabilities are often seen as ”different,” and this can make us a more likely target of bullying.

Although it sometimes felt that way, I wasn’t always alone. There were kids who talked to me, spent time with me, and invited me to the movies – friends who made me feel smart and important, funny and talented. Having people in my life that made me feel unique in a positive way set me on a path of (disability) pride and self-respect, enabling me to live my life the way I want to with confidence

As I’ve grown up, it’s been really important for my peers to not only be aware of some of the differences between us – about my disability and how I see the world differently – but also the many ways in which we are similar.

A study conducted in the 1990s found that “children’s attitudes toward peers with physical disabilities were the strongest predictors of behavioural intentions to interact positively with a child with a physical disability. Furthermore, children’s attitudes correlated significantly with those held by their teachers, principals, and mothers.”

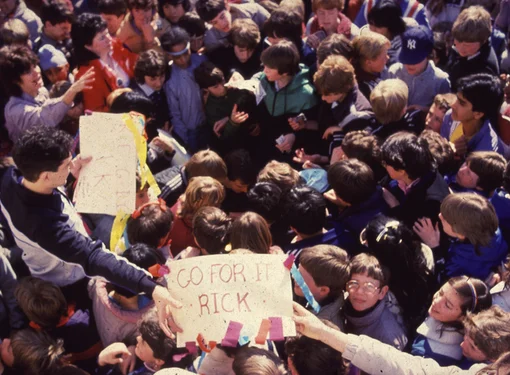

When I started working at the Rick Hansen Foundation, I became particularly inspired by the work of the Rick Hansen School Program, which aims to promote understanding, awareness and positivity about people with disabilities and our stories in schools across Canada. If my peers had understood that having a disability isn’t inherently a weakness, and that my story will be just as interesting and complex as any of theirs, I would have felt less lost.

Now I have a degree in English literature, amazing friends and family, and a career that allows me to make a difference. I participate in martial arts, I knit, I enjoy a good Netflix show, and I sing.

If I could go back to that classroom now, I’d ask my peers who sat in silence to be a little braver. When we’re young, there’s so much fear of not being liked that we allow that feeling to be loaded onto a few people, relieved that it isn’t us this time. I’d ask my classmates to show me that they cared. I’d ask them to hang out with me anyway.

To the friends who stood by me, I’d say, “Thank you. Your kindness changed my life.”

And if I could go back and talk to my younger self, I’d tell her, “Show them who you are. Be good to the people who are good to you. But most of all, don’t be afraid of your disability, don’t bow to other people’s low expectations, and above all, be proud of yourself.”

I think that this year’s Pink Shirt Day message sums it up perfectly: Kindness is one size fits all.

About the authour: Rachel Finlay is the Coordinator for the Rick Hansen Foundation's Ambassador Program. She is a recovering bookworm who likes knitting, tea and politics.